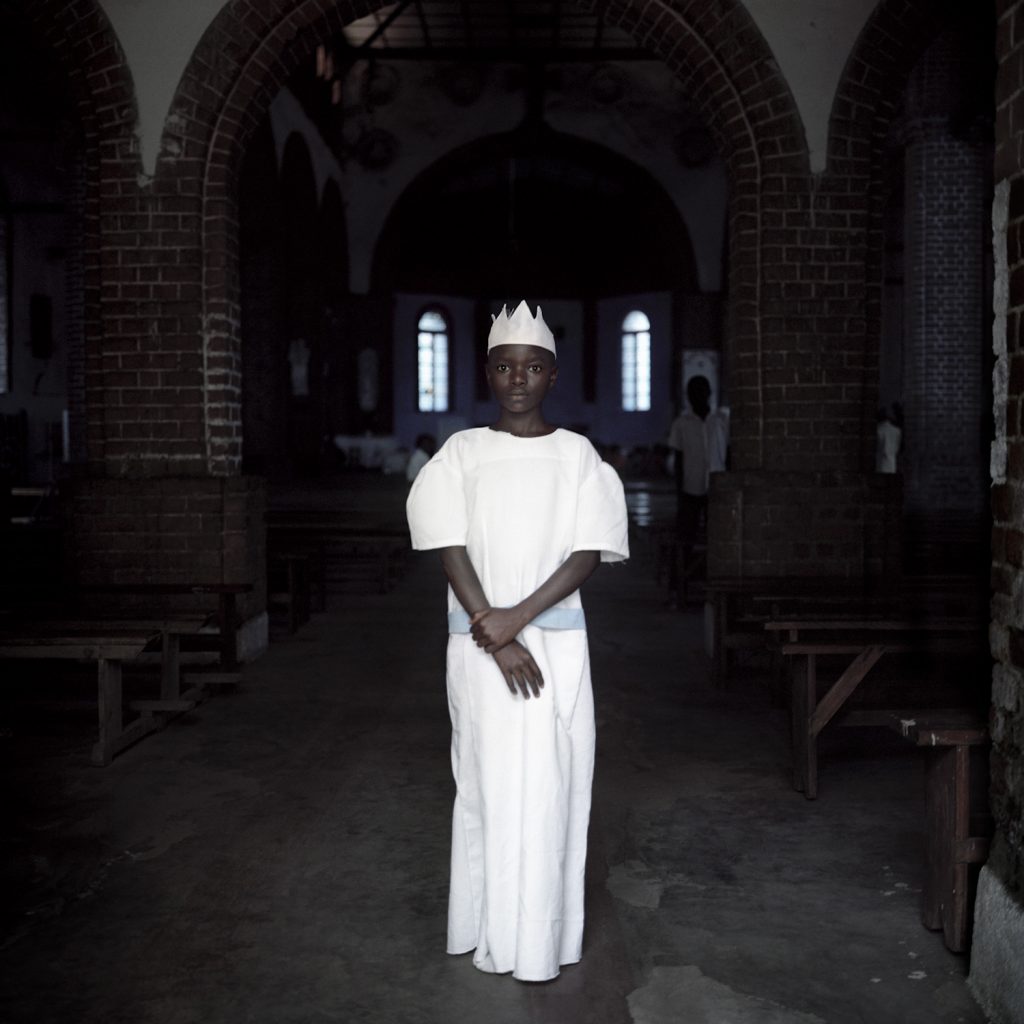

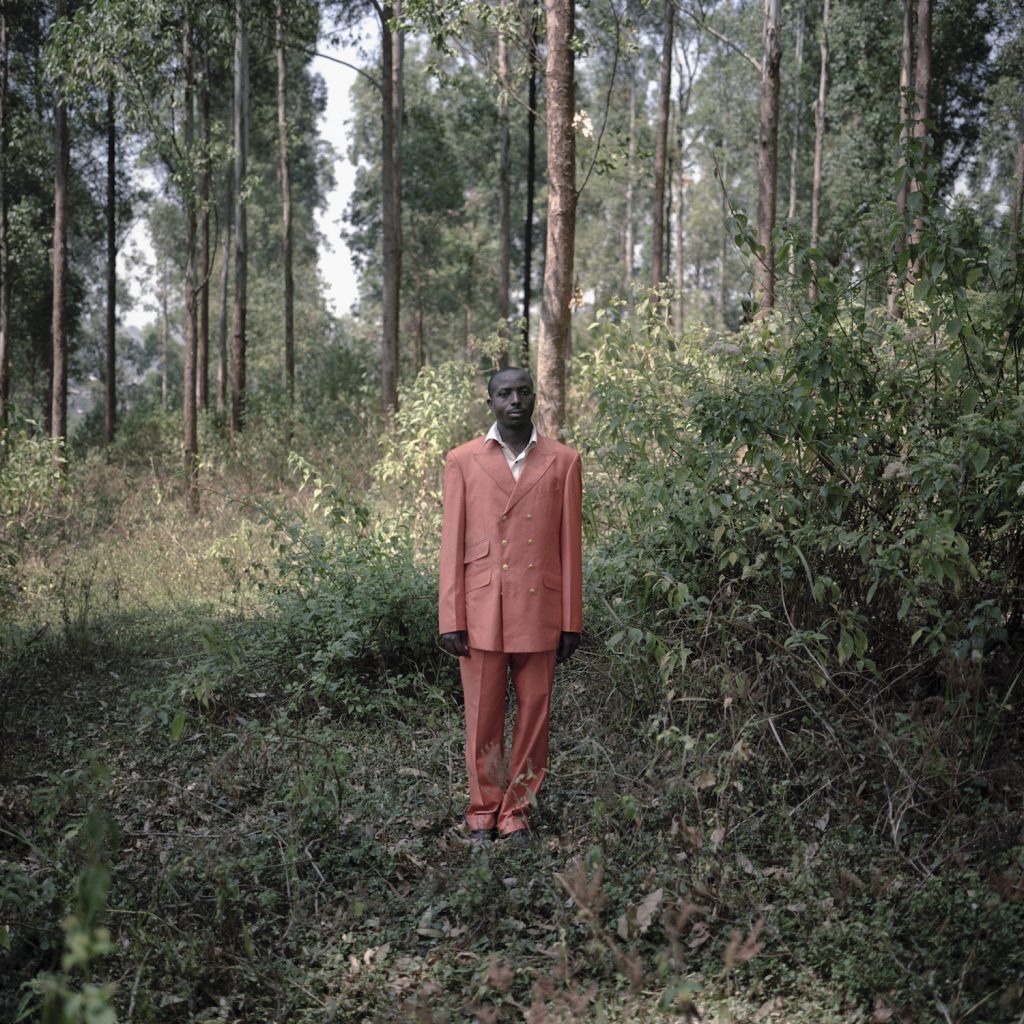

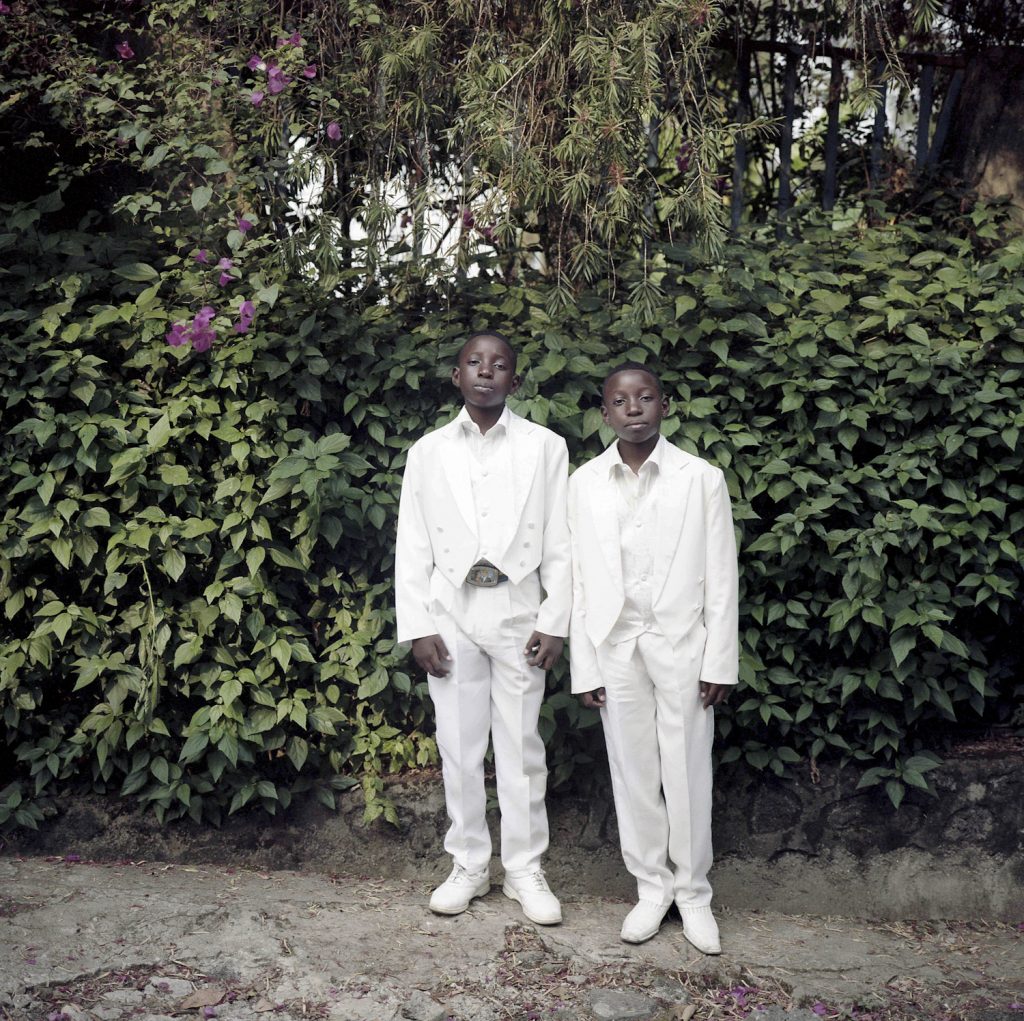

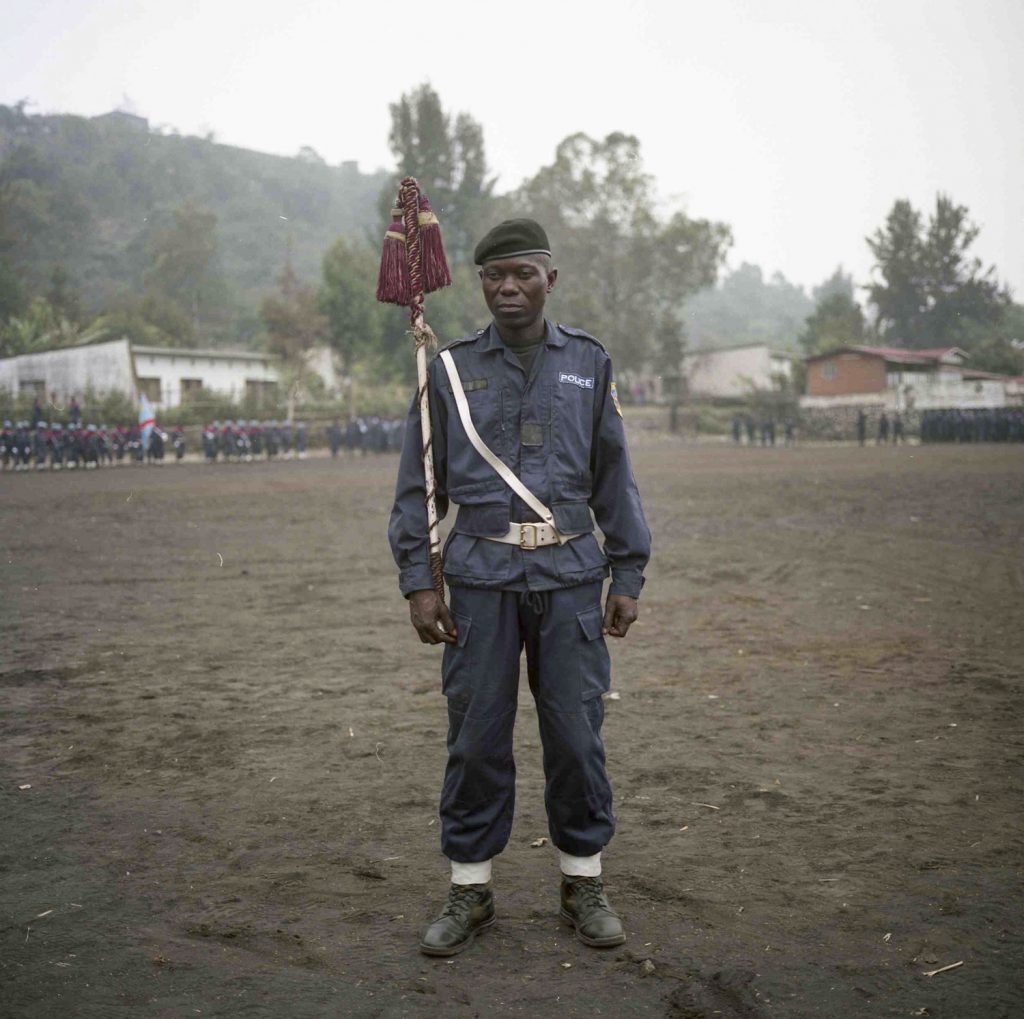

Since Joseph Conrad, the Congo, and more particularly the Great Lakes region, has been depicted as an allegory of heaven and hell on earth. The story that has been written for the past two decades is interspersed with repeated atrocities, large-scale murder and rape, population movements set against a backdrop of sublime landscapes. Despite these grossly repetitive acts of violence, Congalese society has never stopped existing. The population, with an incredible capacity for resilience in this perpetual chaos, continue their daily lives, farming and digging this highly-desirable land. In the streets of the province’s capital, Goma, soldiers, ex-rebels, businessmen and simple onlookers all rub shoulders. Every day, sporting, musical and political events puncuate daily life as in any city on the continent. Hospital delivery rooms are as full as ever and weddings are continuous. Pentecostal churches are flourishing in the valleys and people dance there as frenetically as in Goma’s nightclubs. In this whirlwind of activity, the presence of armed men is practically banal. They could almost merge with the landscape. Except that the daily smell of gunpowder reminds us that peace only exists by default.